ell, this chapter obviously has nothing to do with either the decision to buy the MG in the first place, or its resurrection in the second. But as I was researching restoration techniques in Mike Sherrell's (2) flawless book in appreciation of TCs, I was struck by his claim on p23 that Colin Chapman (1) had "embodied the spirit of the TC in his Lotus Seven Clubman", and had "emulate[d] the TC's essential shape", and - in view of the Seven which we had brought back to Australia with us, and which we still own - I was curious enough to pursue the thought. Were there similarities between the TC and the Seven? Were the similarities enough to justify the claim that Chapman had embodied its spirit? Is there any evidence to suggest that Chapman was thinking about TCs when he and his team were designing the Seven? If he was thinking about TCs, was he thinking of their spirit? And if their spirit was embodied into the Seven, was this embodiment intentional, or accidental; or if not, what could have Sherrell have been thinking of? - could he have been seduced by this more modern legend to find in it attributes of the older which may or may not exist?

ell, this chapter obviously has nothing to do with either the decision to buy the MG in the first place, or its resurrection in the second. But as I was researching restoration techniques in Mike Sherrell's (2) flawless book in appreciation of TCs, I was struck by his claim on p23 that Colin Chapman (1) had "embodied the spirit of the TC in his Lotus Seven Clubman", and had "emulate[d] the TC's essential shape", and - in view of the Seven which we had brought back to Australia with us, and which we still own - I was curious enough to pursue the thought. Were there similarities between the TC and the Seven? Were the similarities enough to justify the claim that Chapman had embodied its spirit? Is there any evidence to suggest that Chapman was thinking about TCs when he and his team were designing the Seven? If he was thinking about TCs, was he thinking of their spirit? And if their spirit was embodied into the Seven, was this embodiment intentional, or accidental; or if not, what could have Sherrell have been thinking of? - could he have been seduced by this more modern legend to find in it attributes of the older which may or may not exist?

Without doubt, both TC and Lotus Seven are classics. But surely you'ld want more to claim embodiment of spirit? You'ld want to look at things like origins, evolution, cost, purpose, style, materials, designers aspirations, and so on.

Origins There are distinct similarities between the two marques here, although there are also major differences.

It would be fair to say that MGs evolved from the passion of one man, Cecil Kimber, who at the time was was the manager of Morris Garages, the Morris sales outlet in Oxford. The first cars were custom bodies built especially by Carbodies on ordinary Morris stock.

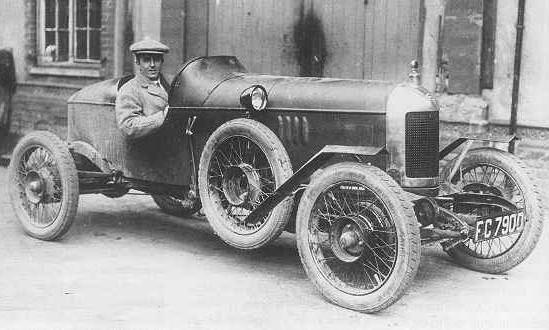

|

| Cecil Kimber posing in Old Number One, in which he won the London to Lands End Rally in 1925. For a better account of the origins of MG and its early history, look here |

During the war years, it seems that Kimber, desperate to find work for the M.G. factory and its employees, negotiated a contract for assembly of the front end and cockpit of the Albemarle aircraft (http://www.mgcars.org.uk/mgcc/sf/000101.htm). Each nose section required as much work as the construction of a complete fighter aircraft, and it is recorded that the innovative solution was a complete success. Nevertheless, his initiative led him into conflict with the Nuffield Organisation who, themselves, specifically Sir Miles Thomas, Chairman, wanted to organise the war work for the whole of the Nuffield factory structure. It would be easy to be uncharitable about Sir Miles's motives; however that was, in 1940 Kimber was dismissed from the company he had founded. (Throughout this paragraph I have drawn most heavily, but not exclusively, on Richard Aspden's book (37) as well as Sherrell's). In 1952, as a result of the merger with Austin to form the BMC, Lord emerged as MD of the new consortium, and thereafter MG's fortunes always seemes to be second to Austin's. Throughout the whole of the T-series production, although MG encouraged participation and provided limited help in the form of tuning guides, MG themselves avoided direct participation and didn't re-enter competition in its own capacity until 1954 when MG agreed to attack the 1500cc class records in order to retain the valuable US market. This successful campaign led directly to the MGA. So TCs were never intended as racing cars, although their bloodline was derived from very successful competition cars. And because the cars were strong and engines amenable to development, many cars designed and sold as road cars were prepared privately for competition, and MG always encouraged this: much of their success and reputation came from such private campaigns. Some 10,000 TCs were made, something over 2000 of them to be exported to USA to satisfy the post-war government's need for hard currency (and about 30,000 TDs were made, some 20,000 of them going to USA).

| I've come across this picture of Hazel Williams in the Mk III in a number of places, but I give credit to www.historiclotusregister.co.uk/thecars/ Halliday.htm |

| Lotus Mk IV. Notice the traces of MG styling - fold-flat windscreen, scuttle fairings, windscreen wiper. This picture also came from the Historic Lotus register, who also have pictures of the MK I and Mk II, but in my view they're both so ugly I couldn't bring myself to copy them |

| Could this have been the original Lotus Mk VI, the first of Colin Chapman's production cars, looking, with its immaculate all-aluminium body, more like the Special it really was than a production item? Compare the headlights, the shape of the bonnet, and the shape of the nosecone to later sixes; and notice the simple one-dimensional curve of the front cycle wings, like the Mk III, not shaped to the wheel as they were in later VIs. Of course you can't see it here, but the fold-flat windscreen has gone, as has the scuttle fairing on the passenger's side. I found this picture at www.simplesevens.org/history/ 50yrsEng/index.htm |

| A later Mk VI. Here you can see that the fold-flat windscreen has gone, the headlights are where we feel entitled to expect them to be, and the scuttle fairing has disappeared from the passenger side. Both fairings disappeared in the Seven. Notice the windscreen wiper, mounted on the top of the windscreen and operated by a switch on the motor, just like the old MGs. I took this photo on the floor of Caterham's showroom. |

Lotuses Mk VIII, IX, and X aren't really part of this story, except to note that they were all developed with minor modifications on the Lotus Mk VI chassis, all used Chapman's rule-bending split front axle, and all were fully streamlined, aerodynamic cars (actually the Mk X gives me one more opportunity to draw a contrast between Lotus and Porsche: actor James Dean was killed in his Porsche 550 Spyder while awaiting delivery of his Lotus Mk X (39)) . Experience with these led to the very highly successful Eleven, also based on the Mk VI chassis, and which still had the split front axle and was still offered with Ford 1172 sidevalve engine (although I can't understand why anyone would ask for that, when eg the Coventry Climax 75 bhp engine was also offered). The Lotus Twelve, though, is part of the story, because this single seater, intended for Formula 2 racing, offered for the first time double wishbone front suspension, using the Standard 10 upright and a Lotus top link incorporating the antiroll bar, and independent rear suspension using a trailing link and using a combined spring/damper unit as the upper link; the assembly was located laterally by mounting the differential rigidly onto the chassis, and drive to the wheels was via half-shafts with universal joints at each end.

In 1957, responding to market demands for revival of the Mk VI for clubman events, Lotus brought out the Lotus Seven. Notice the nomenclature here - the Mk VI, then the Mk VII which was never finished, and the successful Mk VIII, IX, X. At this stage Chapman stopped using Mk numbers with Roman numerals, and started spelling out the name. Therefore the Eleven and Twelve. And out of sequence, but showing astute marketing, the Seven, using the number left vacant by the aborted Mk VII, and cleverly following the MK VI which it so resembled (and from which, ultimately, of course, it was descended, and as a replacement for which the market had demanded the new car).

| Another Mk VI - this time 1955. In this case the owner appears to have replaced the headlights, and the wipers are mounted on the scuttle like a real car. |

| Another picture of the Lotus Mk III, this time with a later Mk VI. Source: Graham Capel (38). Capel's picture was much better: the graininess is due to my scanner |

So I'm not sure that Chapman's men were thinking about anything but a successor to the VI, which would be as successful as they could make it. I don't think they had time to think about TCs at all.

Essence of Sportscars - Shape and Style There were some superficial styling similarities between Lotus Seven and TCs (sadly not including MG's fold-flat windscreen: how good would that have been on a Seven). For example, the separate headlights, incorporated in the Lotuses to meet the bare minimum requirements for clubman cars, which had to be suitable for road use (in fact in the early Sevens you could see that the lights were never intended as serious devices for showing the way at night: the near side light was a fog light with a horizontally spreading beam, while the driver's side light was a spotlight. Dipping the lights simply turned off the light on the driver's side, as was allowed by the road rules at that time, leaving the driver almost blind. Happily this changed sometime during Series 2 production). For another example, the front cycle wings in the Sixes and early Sevens, very similar to the cycle wings used on M- & J-types and early racing MGs like the C-type. These were replaced by the clam-shell wings in order to gain access to the American market, not incorporating running boards but otherwise very reminiscent of the sweeping mudguards first introduced on the MG J2 in 1932 and retained by MG until TF production stopped in 1955. For yet another, the streamlining fairings on the scuttle: these appeared on MGs as early as the racing C-type, and on early pictures you can see how they were crudely grafted onto the M-type body. The fairings stayed on MGs right up to the demise of the TF. In contrast, the Lotus Mk IV had very similar fairings, but first one disappeared on the VI, and the second disappeared on the Seven giving it the familiar straight profile. And finally, early Sixes had a windscreen wiper motor mounted on the passenger side at the top of the windscreen, a feature which MGs kept all the way through TD production, not disappearing until the TF in 1953. And that, it seems, is the extent of styling similarities. While MG kept on tarting up their offering with comparatively minor changes all the way from J2 until the introduction of the radically different style of the MGA in 1955, the Lotus Seven differed only slightly from the Six, and its style remains unchanged today.

Several authors, trying to describe that indefinable shape, made comparisons with other cars - "Why, it's just like ...." - but on reflection the comparisons never quite seem plausible. For example, in his paper Eoin Young went on to say that "you get the same wind in the hair fun from £3000 of Lotus Seven as you do from £30,000 worth of vintage Bentley" (could you really get a Lotus for £3000 in 1978? - or for that matter a vintage Bentley for £30,000? and if you could get one, wouldn't the insurance rather put a crimp in the fun?), and "it doesn't take a very determined flight of fancy to imagine the lights are P100s and the long louvred bonnet is that of an SS100 Jaguar. It really is a fourwheeled version of a superbike with many of the attendant stimulations for the arteries" (the four-wheeled motorbike was obviously a popular joke at the time, and has been used more than once - Autocar (18), 1970; Eoin Young,(5), 1978; Csaba Csere (7), 1982, showing that he can maintain the corporate line from Autocar; and no doubt many others. I heard it first from my neighbour in Harrow in about 1968, and most recently a few weeks ago from a one-time friend at the yacht squadron here in Sydney.)

|

The same "Wind-in-the-hair fun" from le camion le plus vite? I don't think so. Still, while driving on public roads somewhere near Harrow in UK in my first Lotus7 in 1968 or 69, I did meet a 3l Bentley like the one pictured, and did get an unsolicited wave, so they must have seen some kinship; and moreover Caterham matched a 3l Bentley with a Seven in a publicity photo in about 1973. But louvred bonnet or not, could you seriously have imagined the Lotus's glow-worm lights were P100s? And notwithstanding its origins from Swallow Sidecars, can you really see the SS Jaguar as a superbike? And if you were driving a Lotus, why would you pretend to be in a Jaguar? |  |

193-60.jpeg) |

| source: www.frazernash.usa.com |

.jpeg) | A 1957 Frazer Nash and a 30-98 Vauxhall. At least the Nash was designed for minimum weight and maximum performance; but, I don't know about you, apart from that I really can't see much similarity between either of these and a Seven. All they seem to have in common is separate headlights and open tops, and the Vauxhall is basically civilised. It has doors, buttoned upholstery, and although you can't see it in this view, it even has a wicker picnic basket strapped to its back, for goodness sake. |

| A Type 37 Bugatti such as Chapman's early Lotus beat at Siverstone on its first outing |

|

|

|

| Perhaps Phipps and Davis meant a J2 like the two on the right, or even a J1 like the bottom left picture (only 12 were built, and only 3 with trial bodies), not a K2 like the picture top left. There were a few styling similarities, like the step-over-doors, the cycle mudguards and distinct rear mudguards. Notice also the two fairings on the scuttle of the J2, and compare to MGs and early Lotuses. There were other similarities: Like Chapman, Sydney Allard built his motor empire from humble beginnings with one-off trial cars for his own use. Allard's J1 was 1946, while Chapman's first car was also 1946. Allard's had a divided front axle, like Lotus. Both used Ford engines. And with eery prescience, pre-empting Young's analogy by several years, Motor magazine wrote that the J2 was "the finest sports motor bicycle on four wheels ever conceived"). But there the similarity ended: the Allard weighed 22 cwt and used a 3.6l V8 Ford, while the Lotus Mk3 weighed about 6 cwt and used a 1172cc sidevalve Ford. Another point of difference is the price. I saw this 1951 P1/J2 replica (first registered in Jul 1952) in Feb 2009 at the Fazazz showroom in Christchurch, where it was on sale for (gulp) NZ$95,000, marginally more than the best Seven I have ever seen offered! References: www.allardownersclub.org; www.classiccarsmagazine.co.uk |

| I'd say cancel the subscription to Road & Track (22). This was the 1935 Chaparral; it was recalled due to problems with the fuel system - not good when you can't really step out and walk away. Perhaps Girdler was thinking of Jim Hall's seriously sexy 1961 Chaparral Mk1 or his even sexier 1963 Mk2, which might have been better compared to later Lotuses? |

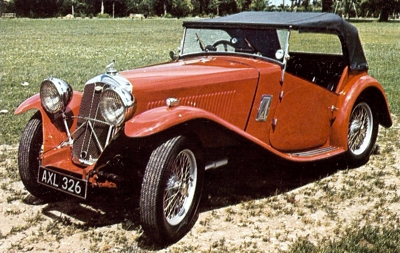

Sports Car World (26), reviewing the very first Seven imported into Australia, reported soberly enough that the lights had been taken from an MG TC and suggested that Colin Chapman (1) could be legitimately compared with Ettore Bugatti. A few months later, J. L. Scheftstik (27), writing about the very same car, may have drawn his inspiration from the same well when he reported that the lights came from an MG TD but nevertheless thought the car looked like a combination of a Formula 1 Lotus and an MG TF (!), and considered that Chapman should be compared not only to Ettore Bugatti but also to to Ferdinand Porsche, Marc Birkigt (from Hispano-Suiza) and Ernest Henry (presumably not the Ernest Henry who discovered copper at Cloncurry in 1867, but the Ernest Henry who is credited for the success of the Peugot and Sunbeam engines in the 1910-1920s). (Actually, on examination, these comparisons do have some merit. In 1950, although intended for hill-climbs, Chapman's second car - only later designated the Lotus Mk II - convincingly won its very first race, beating a Bugatti Type 37 in the process. In 1954, a Lotus MkVI fitted with a 1.5l Ford engine, together with a streamlined version of the same car fitted with a 1.5l MG engine, both beat the works-prepared Porsches in the sportscar race before the 1954 British Grand Prix at Silverstone. Chapman was inducted into the International Motorsports Hall of Fame (28) in 1994, same year as Enzo Ferrari, while Ferdinand Porsche wasn't inducted until 1996, and Ettore Bugatti had to wait till 2002.)

Now, what these authors have done is to identify and emphasise the similar shapes of all these cars. Their shape and style is driven partly by fashion, partly by available technology, but mostly by the front engine, live rear axle design shared by these and almost all other cars of the time - four wheels, mudguards (either cycle or flares), separate headlights and sidelights mounted on the mudguards, and no streamlining. No doubt they could have adduced many other examples - Morgan, Singer Le Mans, Riley Nines, Wolseley Hornet, and so on. Their form is driven by function. Manufacturers struggled to make some points of stylistic difference, with greater or lesser success.

|

|

|

| These pictures of a 1933 Riley Brooklands, a 1940 Riley, and a 1934 Wolseley Hornet all came from the web, but I photographed this Singer Le Mans at the All English Car Club Display Day at The Kings School here in Parramatta |

Essence of Sportscars - Image Notwithstanding its popularity - this Lotus is possibly the most replicated car ever (Birkin, Chevron, Domino, DSK, Fraser, Gibbons, Leitch, PRB, Westfield, and in fact Wikipedia (3) lists fortyfive replicas and claims there are at least 160 copies or very close look-alikes, and in fact at one stage in the 1980s Caterham threatened to sue Westfield based on industrial design rights due to too close a similarity) - the Seven seems to defy description. From consideration of appearance and presentation alone, leaving performance aside for the moment, its uncompromisingly purposeful appearance - almost aggressive - seems, like the TC, to evoke a deep folk memory of how sports cars ought to be. The memory seems to be so deep and visceral that perhaps it relates more to the idea of sports cars than of actual cars themselves. Several authors appear to reflect this view. For example Car & Driver's (4) review said "if you think of it as a car you'll be disappointed", and seven years later Eoin S Young (5) thought they were "not really cars in the ordinary sense of the word, more a frame of mind". Allan Girdler (6) saw it as very much an English car - "had it been any more English it wouldn't have been a car at all". William Jeanes (8) put it pretty well some time later when he described the Seven as "a rolling anachronism guaranteed to bring a smile to the face of every string-back forever mired in the swamp of sports-car nostalgia". Well, that would be me. Miles even likened a ride to a flight in the front cockpit of a Tiger Moth (11). But for my money Csaba Csere (7) nailed it when he described it as "The last and best of true roadsters: it was the purest embodiment of the the maximum-performance, minimum-comfort, no-barriers-to-the-environment school of sports-car design".

|

Well, you can see what Miles (11) meant when you consider the uncompromisingly functional appearance and spartan accommodation of a Tiger Moth, with minimal instrumentation, exposed space-frame construction in the cockpit, plain seats, step-over-the-side doors, and absolutely no unnecessary weight. And Kevin Murphy (19) could easily have been writing about a Seven when he wrote "Whatever magic there is in having the wind whip by one's ears in an open cockpit, the deHavilland D.H. 82 Tiger Moth must have it in abundance, if one judges by the many aviation clubs around the world still dedicated to the aircraft". |  |

Many others tried to define the image of the Lotus, using whatever analogies seemed helpful. Jeanes thought "it runs like a pit bull on industrial strength amphetamines". Chris Beck (9) thought it looked like a praying mantis (but went like a D-type Jaguar), and a few years later Jim Gilbert (10) also thought it looked like a praying mantis, but he thought it went "like a locust through a farmyard". More poetically Miles (11) compared it to a hardy mountain flower. Richard Bremner (12), using his imagination to the fullest, thought that "like sex, the Seven provides a rich sensory experience: it accelerates like a catapulted missile, it corners like a roller coaster; and it sounds as exciting as a rock concert". Much later Nick Kurczewski (13) also compared it to a rollercoaster: "Imagine sitting in the front row of a rollercoaster, and being able to steer". William Jeanes (14) (same William Jeanes, writing this time for the opposition) thought it had the utility of an elephant gun and the irresistible attraction of free champagne. (Of course, at this time Csaba and Jeanes et al would have been writing about the Caterham Seven, the license to build Sevens having been transferred to Caterham in 1973. The license included jigs, existing stock, chassis, drawings and goodwill, rights to the name Super Seven, but not to the Lotus name. In fact, as Jeanes (8) said earlier, the Caterham Seven is "the genuine, copyrighted, signed-sealed-and-delivered successor to the Lotus Seven brought to life by Colin Chapman in 1957". Therefore in this essay I have made no distinction between the Lotus and its legitimate progeny. Now, nearly 50 years after its introduction, Caterham are still producing Sevens, making it, by that criterion at least, perhaps the most successful car ever).

Comfort is not part of the image, as Autocar (23) articulated so clearly: "The producer of an out-and-out sportscar is fortunately relieved of the responsibility for providing too many creature comforts in his cars; Caterham take their lack of responsibility rather seriously". John Bolster (24) observed that the Super 7 was so low you could trip over it in the dark (as I have done). Chris Beck (9) thought it had the comforts of a gaol cell. Jeanes (8) (again) thought it was a "roadster fitted with all the comfort and convenience items you'd find on an anvil", and provided "that essential element of discomfort so you know you must be enjoying it". Tony Pepperell (25) thought the car "possessed looks only its mother could love". Even the Motor Sport staff couldn't resist an unkind shot in their article (15) when they wrote "Some people liken driving a Lotus to a visit to the dentist - it's awful while it's happening but wonderful when it stops - but these people are seldom Lotus owners and if one is a Lotus owner then one is prepared to make many sacrifices such as pre-war Bugatti owners must have done".

And inevitably there were many comparisons with Morgan: indeed I have been asked many times whether my Lotus were a Morgan. Autocar (33) sorted it out for me: "for all their superficial similarity, these two revised versions of existing cars are at opposite ends of an anachronistic branch of motoring: whereas the Caterham has been continually developed to remain at the sharp end of modern dynamics standards, the Morgan clings stubbornly to its traditional qualities". But give the last word here to Miles (11), in the 1980 column referred to above: "the Lotus has tolerable ride quality- at any rate better than a Morgan".

All these things seem to me to talk to the essence of English sports cars, and they seem to agree that whatever it is, the Lotus has it.

But does the TC?

I'm going to suggest that against most of these parameters, the TC doesn't; but it does offer other advantages.

Sherrell implies that TCs excel in quality, mystique and purpose, and goes on to highlight its social versatility and sporting purpose. I'm going to suggest that social versatility should be no part of a sports car's job description. But it'ld be hard to argue against its mystique: after all MGs had been developing their reputation for more than thirtyfive years. But they were lucky: as Sherrell says, much of its appeal comes from its shape, that of a prewar car built postwar. If BMC's management had allowed MG to develop a completely new car after the war, instead of rejigging the TB, I suggest it would not have had the mystique it undoubtedly had. MGs had been evolving into bigger, more comfortable cars, which were capable of winning Best in Show, while Lotus concentrated on what they thought was important. There is simply not enough stuff in a Seven to win open concours: no chrome, no spectacular radiator, no wire wheels, no leather trim, just functionality! And although they certainly did well in sporting events, especially in gymkhanas and hill climbs, TCs themselves were never intended as competition cars. They were intended as revenue raisers for the beleagured British eceonomy in general, and BMC in particular.

Essence of Sportscars - Handling and Performance

Sherrell says the TC is the only car that is fun to drive on a motorway (for those who enjoy living close to the edge). Just like my TB, "It has that startling ability to move quickly across lanes (as if it moving sideways), find gaps and fill them..." Although Mike attempts to make a virtue of this attribute, it is in fact a vice deriving from the TC's appalling Bishop Cam steering. When it decides to make its sideways move, you had better hope that there is a gap that needs filling.

There have been numerous performance reviews of the Seven, but relatively few giving direct comparisons with other cars. Perhaps inevitably many of those involved Porsche. In their review Car & Driver (4) pulled together data from previous tests on a Porsche 914, Datsun 240Z, Alfa 1750 Duetto and a Series 4 Seven, and found for the Seven on acceleration, braking, fuel economy, but just lagging on price. Autocar (31) reviewed a Caterham Seven and compared it with a number of sports cars in the same price bracket, and found for the Seven for handling, road holding, performance, but against for ride, noise and space. In later review by Autocar (32), in one of the few head-on comparisons, a Seven was compared directly with a Porsche 911 Cabrio. Although the 911 cost about 4 times as much and gave about twice the power, times to 60 mph were identical, and the Seven beat the Porsche to 70 mph, and was more economical, but thereafter aerodynamics took their toll. However whenever the road had bends the Seven seemed to excel - "a hard driven Seven would be hard to shake off on a demanding road". Their conclusion: "Almost four Sevens to one 911 is a silly equation". Along the same lines, William Jeanes (14) gave an interesting perspective: the Lotus's 1640 cc engine with 123 hp + weight of 1220 lb gave a power:weight ratio of 9.9:1, whereas a Mustang GT with 225 bhp and weighing 2900 lb, had a power:weight ratio = 12.9:1 (one hopes he was a better driver than technical writer: what he's calculated of course is not power:weight ratios, but weight:power ratios - the exact inverse, so a lower number is better).

Motor Sport evidently couldn't decide whether handling was good or bad: at first (15) they thought that locked brakes on a wet road would turn it from a car to a toboggan, but later (16) thought it stuck to the road like a limpet and steered with the precision of a micrometer, and later still (17), displaying the memory of a Perth entrepreneur or a Member of Parliament at a Senate enquiry, they changed their minds again and wrote that nobody could call the rear-end traction limpetlike (actually I never thought much of their original assessment: one wet and stormy night in 1984 I hit a puddle on the M5 near Bristol and aquaplaned for about 200 yards, fishtailing wildly up the motorway until I sideswiped a VW Beetle and ended up in the drainage ditch beside the fast lane, all the while looking up at the wheels of fully laden lorries as they passed me only about 20mph above the speed limit, and I can tell you that in those conditions you would feel much more secure in a toboggan. When I took the car to the garage to have the suspension straightened, the mechanic told me that anyone who hadn't managed to sideswipe a Beetle wasn't really trying).

In a comparative track test in Oct 2000, the fastest Seven from Caterham was measured against a number of other out-and-out speed machines at the Croft racing circuit, and with the following convincing results (35):

Caterham Seven R500 - 1.31.53 (0-100 kph time of 3.4 seconds, top speed of 243 kph)

Yamaha R1 - 1.32.96 ( 1000 cc racing bike with 0-100 kph of 2.8, top speed of 260 kph)

Stealth B6 - 1.35.37

Lotus 340R - 1.35.78

Caterham Blackbird - 1.35.98 (weighing 430Kg & boasting 165bhp)

Nissan Skyline 600 bhp - 1.36.55

Mitsubish Evo VI RS Sprint - 1.40.55

Porsche 911 Turbo - 1.40.95

TVR Cerbera 4.5 - 1.41.22

Ariel Atom - 1.44.80

And finally, in July 2004 Simon Nearn enjoyed pointing out that "Autocar magazine has just done its annual 0-100-0 test and our Caterham Seven R500 evolution was two-tenths of a second quicker than the Ferrari Enzo - and it's just one-tenth of the price; previous winners of Autocar's annual test include the McLaren F1 road car and the Moser MT900S (a roadgoing version of a GT racing car), and this year's competitors included the Aston Martin DB9, Pagani Zonta and Ferrari's Enzo."

Many authors have made several vague and extravagent comparisons (ie no hard data) with other marques. For example Motor (29) reckoned a Seven would "see off such cars as the Lamborghini Countach, Porsche 3.0 Turbo, and Aston Martin Vantage". Miles (11), yet one more time, compared acceleration to non-Vantage Aston Martin V8s, Maserati Khamsin, Porsche 911SC, and Mercedes Benz 450 SEL 6.9. In an interview (30) with Graham Nearn, Patrick McGoohan reckoned the Lotus was "faster than a Maserati and quicker around corners than a Ferrari". In a publicity release in 1989 Caterham Cars claimed the Seven was "still capable of humbling the might of Porsche and Ferrari". Nick Kurczewski (13), in the article already referred, casually mentioned a 0-60 mph time of 3.1 sec and reckoned "The Caterham CSR scorches away with straight-line speed to humble any Lamborghini or Ferrari. A McLaren F1 might keep up, barely. Sounds ridiculous? Frankly, it is!"

Essence of Sportscars - Racing

Well surely this would have to be the most important section in this essay comparing and contrasting these two icons of sports motoring. So important that I'm still gathering my thoughts.

Please check in later and see how they're going. Or if you have some thoughts of your own which should be reflected here, send me an email.

| Not a Type 37, admittedly, and for that matter not a TC either, but to some extent you can see what they meant |

1) Although both Lotus and MG were developed due to the inspiration and commitment of single individuals, their circumstances were very different: Cecil Kimber had a steady job as General Manager of the sales outlet of Morris Motors while he built special four-seater sports-bodied cars for general sale, and was able to draw on the resources of the manufacturing arm to build his product, but in contrast Chapman, while building his first car for his own use in trials, was still at University, trying to run a second-hand car sales business.

2) Lotus were always innovative, pushing the design limits with every iteration, while MG were developed from minor changes to custom bodies on standard rolling stock. (Alternatively, while MGs were patiently developed by improving existing designs, Chapman concentrated on finding new ways around the rules - a trait which arguably may have contributed to the downfall of Lotus in the De Lorean embroglio.)

3) MG quit racing by late 1930s, less than 10 years after incorporation, and didn't resume in their own right till well after production of TCs had finished; in contrast Lotus never quit racing with the Seven, and shortly after Caterham took over manufacturing rights they started their own league to ensure the opportunity for good racing continued. And the Lotus brand, having first been taken over by General Motors in 1983, was later acquired by Bugatti in 1993 (and please don't ask who owns the brand now). When Chapman began to wind back Lotus racing in 1970, it was because he saw Lotus's future, no longer with clubman racing or with kit cars like the Seven, but with F1 racing and with road cars like the Elan, Elite, Esprit, and perhaps even the Europa, competing with the likes of Porsche, Lamborghini and Ferrari. So it's ironic, isn't it, that while the Lotus brand has disappeared in all but name, the Seven itself continues and successfully challenges the very marques for which Chapman abandoned it.

4) Faint as they were, early styling similarities between MGs and the Mk IV and Mk VI had disappeared by the Seven, leaving only the superficial similarity of the front mudguards.

5) Successive iterations of T-types concentrated (rather unsuccessfully) on improving comfort, especially to appeal to export markets; in contrast successive iterations of Sevens concentrated only on performance and handling.

6) During the 19 years of production, T-types used only one engine, the XPAG, admittedly with minor developments like provision of a timing chain tensioner on the TC (and why, oh why didn't the engineers specify the beautiful, race-proven Riley Nine engine, which must have been available to them, instead of the mediocre Wolseley unit: when the Riley group of companies was acquired by the Nuffield Group in 1938, the Riley engine works were not included in the deal, but for a while they continued to supply engines to Nuffield for the continued production of Rileys. In 1947, in a move reminiscent of Kimber's dismissal, Victor Riley was dismissed from his company, but BMC continued to use Riley engines well into the 1950s). In contrast Sevens used whatever was currently the most powerful engine, and when no suitable engine was available they developed their own or encouraged spin-offs (eg Cosworth. Both Mike COStin and Keith DuckWORTH initially worked full-time at Lotus. When Duckworth left Lotus to set up his own engine tuning company, Costin, who was in charge of engine tuning at Lotus, stayed with Lotus but owned shares in Duckworth's company, and later left Lotus to join him. The Cosworth modified engines were initially offered only to Lotus, but they were so successful that in 1968 Lotus were ordered to make them available to the competition.).

7) Although developed from the Eleven's chassis (itself developed from the Mk VI), the Seven's chassis was made especially for the Seven, providing unprecedentedly taut handling; as engine power has increased, Caterham have added strength to the chassis. In contrast, except for minor changes eg spring shackles instead of sliding trunnions, although engine power increase significantly, the TCs chassis was essentially unchanged from the 1929 M-type allowing chassis flex, axle tramp, uncertain steering, doors that can fly open when the body flexes, and all the other sins.

8) TCs were a serious production item for MG, and for the British Government. They were exported to US in considerable numbers to satisfy the Government's need for hard currency after the war. In contrast, US was never a target market for Sevens, and those few that have ended up there are due to efforts of committed individuals. Sevens were and are a niche market: "We don't have grandiose ideas. We want to continue developing our niche market: we can't do what BMW do, and they can't do what we do. We like to think we're a credit to the fundamental design of the car and guardians of the Lotus 7 legend. As long as there are free spirits, people will want true Sportscars like the 7." (Simon Nearn) (44)

9) Cecil Kimber set the initial direction for MGs, but the fortunes of MG in general and TC in particular were hostage to the changing whims of the British Government and the various owners and managers of Morris Garages, Morris Motors, British Leyland, BMC, etc; and Kimber died a disappointed and frustrated man. The initial direction of Lotus in general and Sevens in particular was set by Colin Chapman; and when his judgement faltered, the compass was carried and the course was set by Graham Nearn. Chapman died just before the facts of his involvement with John De Lorean became known, which may have been one of the factors contributing to Lotus's eventual demise. The engineering and development of De Lorean's car was primarily done by Lotus. The entire suspension and frame was borrowed from the Lotus Elan, and much of the styling was borrowed from the Esprit. Much of the money that "disappeared" from De Lorean Motors was suspected of having been siphoned into Lotus (40). It has been said that it was probably fortunate that he died when he did and thus avoided the scandal which was later revealed about Lotus's involvement with the Delorean car company. A judge later remarked that if Chapman had been alive he would have been sent to jail for 10 years for an "outrageous and massive fraud" (41). To give De Lorean the credit he deserves, though, wasn't it a brilliant attempt to bail his company out? If only he'd had private shareholders, not the UK's National Enterprise Board (42), (43).

10) Lotus produced the Seven for fourteen years. When Chapman finally decided the marque had run its course, Graham Nearn from Caterham asked for and received a license to keep manufacturing the Seven; and todays Caterham Seven is legally and recognisably the descendant of Chapman's Seven, which is therefore still in production after nearly 50 years (at the time of writing), almost unchanged except for a brief hesitation for the unsuccessful Series 4.

11) TCs were manufactured for only four years; but if you count the entire T-series (including the TD with its radically different chassis/suspension and the mechanically identical but stylistically different TF) it lasted from 1936 till 1955 with a short break for the war (ie 19 years of elapsed time, but only 14 years of production). When TCs - or indeed the T series in general - stopped production, no-one asked for a license to keep manufacturing (but in 1986, an Australian manufacturer made a fibreglass copy of the TD - the TD2000 - on Nissan running gear and in 1998 the rights, intellectual property and trademarks were licensed to TD Cars Sdn Bhd in Malaysia, and as far as I can tell is still being made).

So now I feel ready to answer the original questions:

I see no evidence that Chapman even thought about TCs when designing or marketing the Seven, or set out to incorporate the spirit of TCs into the Lotus Seven, and indeed no evidence that it has been so incorporated. No doubt Sherrell saw attributes of the TC in the Seven, and may well have imagined more; these would have been success on the track, and the anachronistic discomfort particular to the British way of life and their pre-war sports cars in particular. I can't think of anything else.

References

This list of references looks more impressive than it might have done, and compiling it has been easier than it might have been, because I have drawn heavily on the compendium "Lotus & Caterham Seven Gold Portfolio 1957-1989", compiled by R. M. Clarke and published by Brooklands Books ISBN 85520 0007

(1) Colin Chapman, http://www.speedace.info/lotus.htm

(2) Mike Sherrell

(3) www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lotus_Seven

(4) Road Test: "Lotus Seven Series IV", Car and Driver, Nov 1971

(5) Eoin S Young, "The Lotus Seven Frame of Mind", Autocar, Jul 15 1978

(6) Allan Girdler, "A Street-fighter Racer", Road and Track, Nov 1984

(7) Csaba Csere, "DSK 7 Turbo", Car & Driver May 1982

(8) William Jeanes, "Caterham Super 7", Car & Driver, Sep 1988

(9) Chris Beck, "The Sensational Super Seven", Sports Car World, Feb 1964

(10) Jim Gilbert, "The Kit Car that Made Good", Road Test, October 1970

(11) Miles behind the Wheel, "Seven Sensations", Autocar, Jan 26 1980

(12) Richard Bremner, "Seven Deadly Spins", Motor, 30 March 1985

(13) www.edmunds.com/insideline/do/Features/articleId=108353.html

(14) William Jeanes, "Caterham Super Seven", Automobile Magazine, May 1988

(15) Motor Sport Staff, "Building and Running a Lotus Super Seven", Motor Sport, March 1963

(16) Editor, Motor Sport, "Rumblings", Motor Sport, July 1970

(17) ML, "Road Test: Caterham Seven 1700 Super Sprint", Motor Sport, September 1985

(18) Autotest, "Lotus 7 Twin Cam SS", Autocar, 29 Jan 1970

(19) Kevin Murphy, http://www.warbirdalley.com/tiger.htm

(20) Road Test, "A Ball of Fire", Autosport, Jul 5 1979

(21) David Phipps and Mike Davis, Road Test, "Lotus Seven", Sports Car Illustrated, June 1960

(22) Allan Girdler, "After the Numbers Wear Off", Road & Track, April 1968

(23) Test Extra: "Super Seven", Autocar, Sep 1975

(24) John Bolster, "The Lotus Super Seven", Autosport, 29 Sep 1961

(25) Tony Pepperell, http://www.constructorscarclub.org.nz/Articles/whatisitaboutthe.html

(26) "Lotus with Split Personality", Sports Car World, August 1961

(27) J. L. Schefstick, "Amazing Lotus Mk Seven", Australian Motor Sports, Dec 1961

(28) Hall of Fame, http://www.motorsportshalloffame.com/main/03_halloffame.htm

(29) Unfortunately I have lost this reference in entirety, except for the quote. My notes say April 1978, but this cannot be right. Any help would be appreciated.

(30) Interview, http://www.theunmutual.co.uk/interviewsnearn.htm

(31) Road Test: Seventh Heaven, Autocar, 19 Jun 1985

(32) Nick Carter, Bob Murray, John Mason: "Performance by the Pound", Autocar, 7 Oct 1987

(33) Duel! Autocar, May 25 1988

(34) http://www.conceptcarz.com/vehicle/z8011/Lotus_Seven/default.aspx

(35) http://www.adelgigs.com/history.shtml

(36) http://www.mgcars.org.uk/news/news128.html

(37) Richard Aspden: "The Classic MG", Bison Books Ltd, 1983, ISBN 0 96124 109 6; now out of print

(38) Graham Capel: "Lotus - Historic Half Century 1948 - 1998", Brooklands Books, ISBN 0 9525732 0 2

(39) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Dean

(40) http://www.dmcnews.com/faq/h_lotus.htm

(41) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colin_Chapman"

(42) http://ateupwithmotor.com/model-histories/delorean-dmc-12-history/4/

(43) http://eightiesclub.tripod.com/id305.htm

(44) http://www.themanufacturer.com/uk/profile/4713/Caterham_Cars.html Jul 2004